HUMBLE BEGINNINGS I first hung my producer shingle in 1982; although in truth, it only hung on the door of a spare bedroom. But, I was open for business. I’d just completed graduate studies at what is now the University of Louisiana. At the time video production was a new industry, and a proper facility required a huge capital investment. That kind of facility seemed unattainable or, at least, something to be realized in the very distant future. But, with $1,500 in savings and an $8,500 loan, I took the plunge. A wish list pinned to a bulletin board, seemingly so modest now, hung for years before I was able to scratch off the last “critical” piece of equipment.

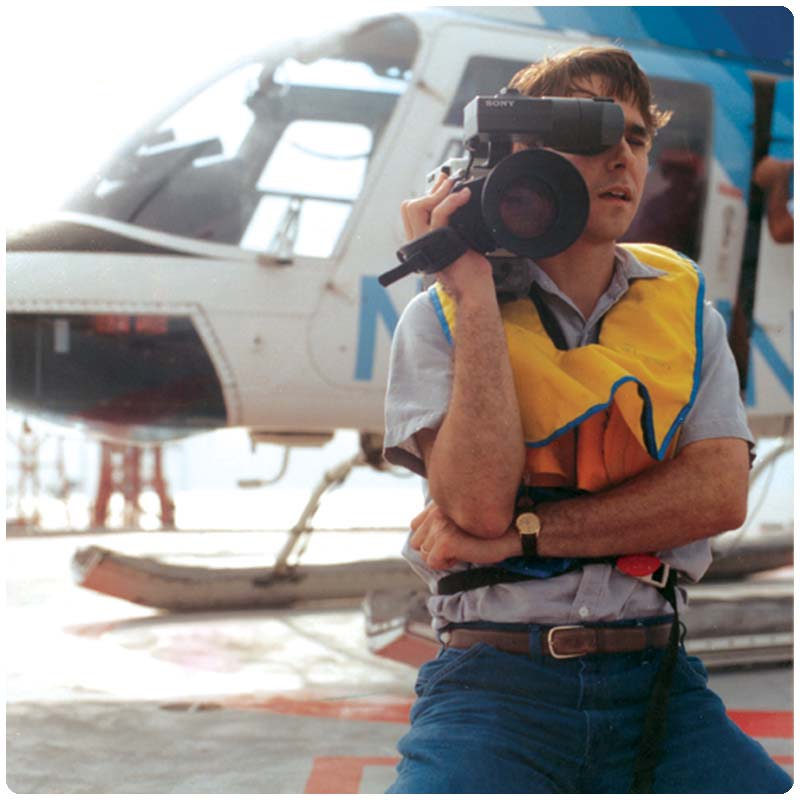

For the first few years, determined to succeed, I took any work that paid—weddings, baptisms, high school football games, and small commercial projects. Although this type of work wasn’t the ultimate goal, the experience was valuable. The gulf coast oil bust of the mid eighties, which decimated Lafayette’s economy, helped to make the early years quite lean. I remain grateful to my wife Tammy for her patience and support, and of course for her vital teacher’s paycheck.

EARLY GROWTH It’s difficult to remember a time before the Internet, but in the early years, information was fairly difficult to come by. The production industry at the time, particularly field production, was a sort of guild; to a lesser extent, it remains that way today. Apprenticeship was the only practical way to obtain proficiency, and that wasn’t really possible without leaving the area. So growth was slow, but steady, for my one-man band.

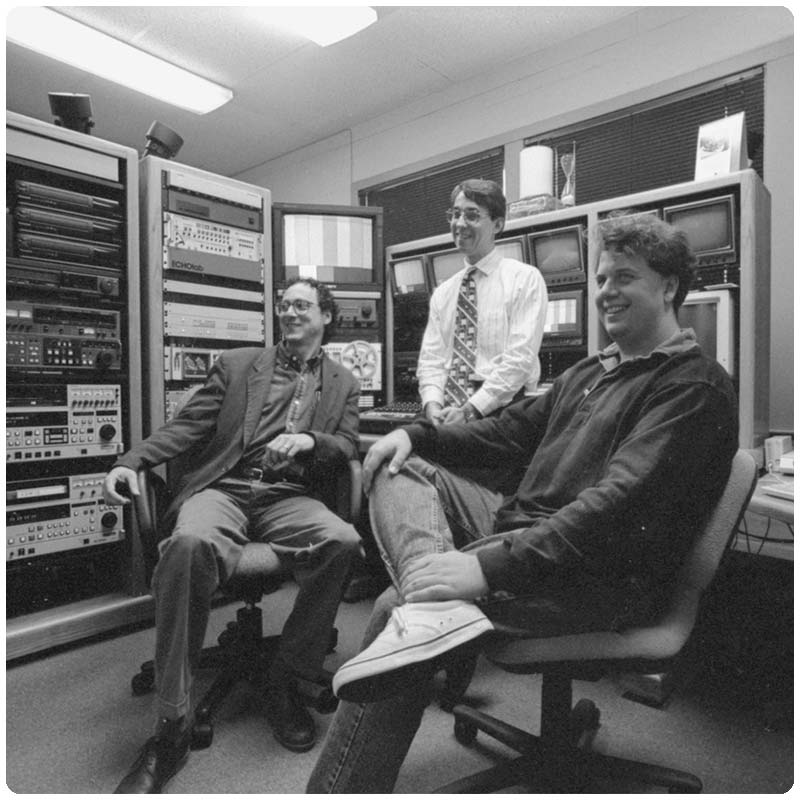

That began to change in 1989 with the hiring of my first employee, and now partner, Scott Rachal. It didn’t take long to see Scott’s extraordinary talent and dedication. Together we pushed forward and truly began to perfect our craft. Over the next decade we continually re-invested nearly all profits, and grew steadily.

Much of the following history of Vidox is the history of the industry over the last three decades. It is by nature technical, but, hopefully, an interesting story nonetheless.

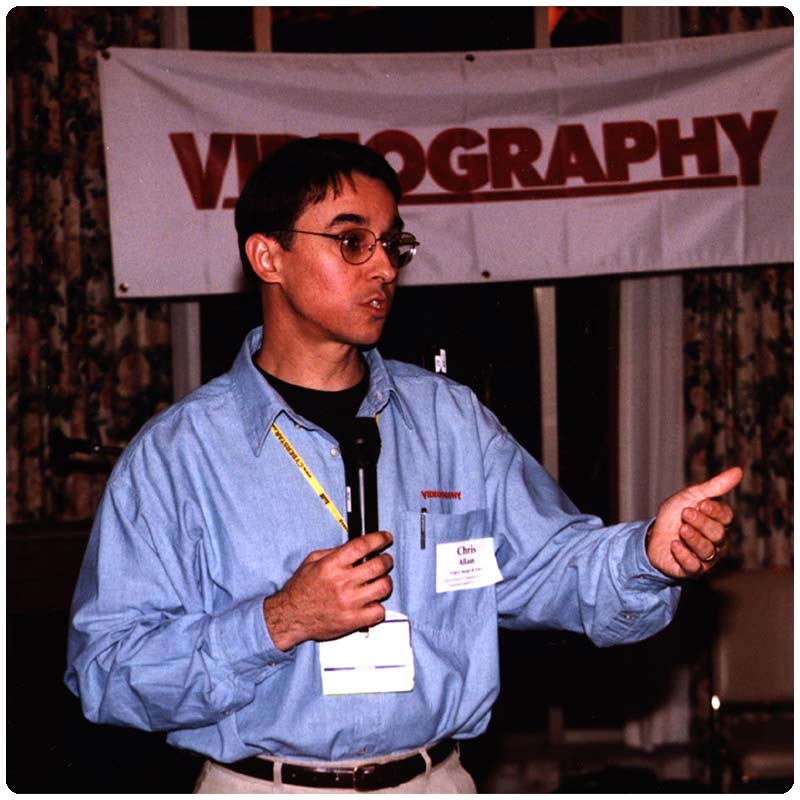

VIDEOGRAPHY In 1991 I began writing for Videography Magazine. Editor Brian McKernan provided me with my first opportunity to write for a national magazine. I am grateful that over the years, he has remained a great supporter, collaborator, and friend. As a Videography Contributing Editor for over a decade, I chronicled pioneering efforts to find and develop digital video tools and techniques for use in our growing business. In the nineteen eighties and nineties, a state of the art video post-production facility might have employed fifty or a hundred individual pieces of equipment—from analog tape machines, to black box signal processors with blinking lights and whirring fans. They generated lots of heat, required lots of power and air conditioning, performed often arcane functions, and oh, were they costly.

Although computers at the time had a small fraction of the power they have today, there were a handful of visionaries with a dream—to adapt the appealing graphic user interface of personal computers, particularly the Macintosh computer, to the processes of post-production. Although bound by the day’s technology, Scott and I relentlessly pushed the envelope in this exciting new direction. The goal was to develop better human interfaces for the process of post-production and to lower the cost of entry.

For years we installed, interfaced, and tested a seemingly endless stream of peripheral equipment, complex video boards, and specialized software. Each new overnight delivery promised to solve the problem du jour. The process required countless, sometimes daily, conversations with manufacturers and developers from all over the country. I told our story in the pages of Videography and in speeches at conferences from Los Angeles to Boston.

OPEN STUDIO In the mid 1990’s, I co-founded the Open Studio Association with Videography contributing editor Craig Birkmaier. Open studio was a technical group supported by major manufacturers like Apple, Microsoft, and Panasonic. This effort ran for several years, as engineers, software and hardware developers, and media producers refined standards for the use of open-system computer technology in video production. Through roundtables and conferences in Las Vegas, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Monterey, Orlando, and New Orleans, Open Studio focused on interoperability—getting devices to communicate and work together.

Open Studio participants were among the earliest to understand something inconceivable to most at the time: a single computer would one day replace an entire edit suite. They led an industry, solving problems one by one, and guided manufacturers toward the solutions they envisioned. Off-the-shelf video production software packages, commonly available by the year 2000, were unimaginable a decade earlier.

As personal computers matured to truly support digital video, Vidox was no longer split between pioneering new technology and using it. Eventually we could focus full-time on producing great media content. A new paradigm for the industry led to a new chapter for Vidox.

AN EDITORIAL LEAP Vidox marked a major leap forward in 1993 with the acquisition of an Avid Technology “Media Composer”. This system was the first widely used “non-linear” digital video editing system available. The Avid allowed editing of video on a timeline using picture icons, an interface style still used today. A non-linear editor was to a traditional linear editing system what a word processor was to a typewriter. It significantly increased speed and creative freedom, but image quality wasn’t acceptable for finishing programs and commercials. Personal computers simply didn’t have the power yet. So most top facilities at the time, made editorial decisions on the Avid, but they would “conform” the edit on-line. An on-line conform was a semi-automated, but tedious re-edit using a conventional “linear” edit suite. The process was linear because each shot had to be laid after the one that preceded it. If an editor had to add two seconds to the beginning of the video, the entire program had to be re-edited.

NETWORK QUALITY Linear video editing is a hugely technical process requiring concentration and great timing and reflexes. An editor would operate in a suite filled with specialized equipment, black boxes, and loads of video tape recorders or “VTRs”. In addition to being an editorial artist, the video editor in 1995 had to be something of an engineer, especially in smaller facilities. An editor in a room surrounded by machines had to know how to work each piece of equipment, how to keep it working, and how to know when it wasn’t.

Although we knew that production technology was changing rapidly, business growth required continuous, though careful investment in conventional on-line equipment. In 1995 we upgraded our facility to a component analog suite including switcher, digital video effects, multiple VTRs, signal routers, and a Digital Betacam mastering deck. This suite represented a milestone in image quality and production capability. For the first time Vidox could produce at “Network Quality”— at the time, the term “Network Quality” represented the holy grail of video production benchmarks.

By the year 2000, Vidox had shifted all of its editing to the latest Avid Media Composer. This system, the first of its kind in the state of Louisiana, allowed uncompressed, non-linear editing at a quality level comparable to an on-line system. The Avid had matured into an excellent, reliable tool and a suite once filled with machines now had far fewer blinking lights and equipment racks. In the years that followed, lower cost post-production systems became more and more powerful and the Avid was, itself, retired to our hi-tech equipment graveyard.

TOOL IMPROVEMENTS In 2003 we traded our cozy 1300 square foot shop for an 8000 square foot office and studio. We went from two parking space to thirty-two. The acquisition and renovation took about a year and the size of the project tested me in ways I hadn’t imagined. Read about that project in the DV Magazine article “This Old Studio”.

Early in 2003 we started shooting high definition video on select projects and a few years later began to edit in HD. In 2007 we moved to shooting HD video on solid-state memory cards and eliminated the use of videotape. A year later we acquired a Panasonic P2 Varicam—a great digital cinema camera used to shoot numerous theatrical feature releases.

That year we also began editing virtually all content in HD even though two years later, in 2010 few area TV stations could even playback an HD spot. Today, 4K digital motion picture systems used by Vidox offer a cinematic look that was once the exclusive domain of the major film studios.

A NEW CHAPTER Throughout the decade tools improved gradually, the cost dropped, and the whirlwind slowed. Revolutionary change gave way to evolutionary change. The next software release no longer had the power to change the game. The tools, once so critical, became almost incidental. The post-production process, once nearly athletic, became more cerebral. In many ways, for the first time, imagination was the limit, and skill mattered most. It was on to a new era of producing motion imagery.

Excellence has always been our mantra and after nearly four decades Vidox has established a tradition as a media production technology leader focused on creating stunning motion imagery and world-class content.

Many thanks to the clients, partners, supporters, and friends we’ve had the pleasure to associate with over the years.